Returns, Revisitings, A Plan?

Late summer's heady stillness has forced me to return home. Taking this week to remind myself how and why I'm writing about museums, and asking what the future holds.

Hello. Long time no see…I’ve had a summer hiatus, but rest assured I’ve been parading my eyes around museums all over the country. I’m now back to a regular posting schedule and over the next few weeks I’ll tell you all about what I saw at the Museum at Tring, the Leicester Museum, Wollaton Hall, the Royal Armouries in Leeds, the Leeds Museum, Creswell Crags, and the Natural History Museum of Lausanne. However, before I dive back in, I want to use this article to remind myself what this blog is about, and why discourse about natural history museums (and all the winding tendrils of things that fall beside them) are important. Whilst I’ve been visiting contemporary museums, I’ve also been spending a lot of time in the archives of the Natural History Museum in London, asking the lovely staff to bring me box after box of photographs of past exhibitions. I’ve taken too many notes and even more photographs of photographs, so today I’m going to unpack some of the stuff I’ve come across.

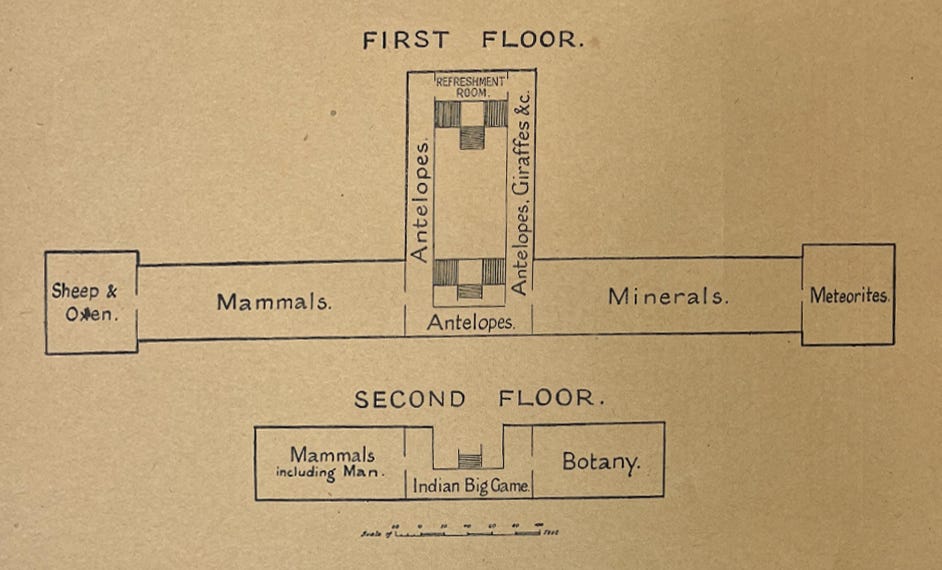

What I was hoping to gain from the visits, more than just satisfying my obsessive compulsion to stare at displays that reached back through time, was to chart a loose understanding of the change in display culture over the past 150 years. So I emailed the library, and several weeks later, after traipsing through the cafeteria and making my way to the very end of the reptile hallway filled with hooting children thrilled to be on summer holidays, I reached the cool, quiet, carpeted lair of the libraries and archives. I was given a plastic card, asked to sanitise my hands, and presented with a box of gloves. The first item I looked at was the ‘Guide to the Exhibition Galleries of 1920’. It painted a picture of a very different museum than the one we can visit today. The floorplan of the central hall showed exhibits of ‘Domestic Breeds’ and ‘Economic Zoology’ which included the skeletons of celebrated horses and various breeds of sheep. These exhibits also featured information about injuries caused by insects to trees, fruits and vegetables produced in Britain, and coffee, tea, and other imports from parts of the Empire. It presented various parasites affecting man and domestic animals and the special exhibitions featured displays such as “The Fauna of Waterworks, Especially the Animals that Block up the Pipes when the Filtration is Inadequate”, “Birds Beneficial to Agriculture”, “British Trees”, and “Plants mentioned in the Bible”.

These exhibits paint a sensible, controlled, and very British picture of natural history, a world away from the pomp of exotica revelled in just 50 years prior* to the guide discussed above. The earliest picture I can find of the Central Hall of the NHM shows a single hippo in the centre, lonely amidst the slanted sun beams in the cavernous, echoing hall. It would later be joined by all sorts of animals from the four corners of the world, acquired through imperial and royal connections. By the 1920s, these specimens would be mixed in with domestic animals, or relegated to the more distant galleries (see ‘Indian Big Game’ section on the second floor of the plans above). The heart of the museum had been turned over to a practical understanding of species in order to reinforce the rationality of the imperial project. By presenting the spoils of conquest as objects for scientific study and advancement, the natural world was tamed not just in the colonies abroad, but in the hearts of English people as well. All over the country, there was a concerted effort around the turn of the century to align natural history museums with contemporary scientific practice (1) and put an end to the showmanship that was the legacy of cabinets of curiosities. Oddities were sold or packed into storage (1) to bolster the hardline scientific cojones of institutions and reinforce that the collections on public display were representative of modern reality, which had traded in mysticism and superstition for cold, unforgiving fact. This new rational image meant museums could wield thinly veiled racist beliefs as empirical (or rather, imperial) truth. In the same 1920 guide, the hall of mammals upstairs is home to an exhibit on “the zoological character of the different races of man, the series including busts, skeleteons, skulls, hair, and portraits. Near them is a fine mounted tiger shot by his majesty the king.” Despite the scientific credits granted by taxonomy and display, underneath the surface very little had changed.

The museum, even in the early days, was conscious of its history. A pamphlet from 1931, when the NHM was still part of the British Museum, acknowledges that its early history is similar to that of ‘most of the great museums of the word. It is the story of the acquisition of great private collections by the state.” (General Guide 1931) Before these ‘great museums’ material history was privately owned, guarded by the church, or still roaming the wild, living and breathing.

“In the middle ages the monasteries, churches, and abbeys were the repositories of unfamiliar natural objects as well as works of art and manuscripts. Thus some ribs of a whale were still hanging as late as the 18th c. in the Schloss Kirke of Wittenberg. Durham Cathedral possessed 2 griffin’s claws brought from the Holy Land.” (General Guide 1931)

The possession of natural history specimens by private collectors and churches meant they were often part of a broader context which included relics, artefacts, art, and other objects. This meant that their existence was justified by their spiritual, political, and financial value as well as their educational one. The Natural History Museum, as many of you will already know, was the personal collection of Sir Hans Sloane, and included “books, drawings, manuscripts, prints, medals and coins, ancient and modern antiquities, seals, cameos and intaglios, precious stones, agates, jaspers, vessels of agate and jasper, crystals, mathematical instruments, [and] pictures,” as well as zoological and geological specimens. (2) Early accounts of the private museums of kings and nobles, like the Schloss Ambras of Rudolf II in Austria show that possession of specimens and artefacts was as much about knowledge as it was about demonstrating power over the known world - creating a microcosm of reality within one’s own home. (3)

The separation of natural history and history proper came later. As collections grew, definitions were refined, and we find 'natural history’ within a museum defined as ‘a collection of objects, both animate and inanimate, found in a state of nature’ in the 1931 guide to collections. (4) There’s two parts of the sentence that make my ears prick. Firstly, the assumption that objects can be animate. Secondly, the assumed definition of ‘state of nature’. Let’s unpick the first idea : The definition implicitly acknowledges that by taking animate creatures - animals - and killing, stuffing, and displaying them, it converts them from subjects into objects. An object is defined as 1. a material thing that can be seen and touched. or 2. a person or thing to which a specified action or feeling is directed. (5) The ‘animate’ objects are to be used to direct feelings at, be they of horror, wonder, excitement, inquisitiveness, or admiration. We see then, subtly, one of the purposes of specimens on display, and gain a clue as to why they are displayed just so. It is to facilitate a projection of audience emotion. The idea of a ‘state of nature’ is a complex one as well, because even though I’m of the belief that modern industrial society is as much a part of nature as an untouched bit of rainforest, I know this is not what the authors of the definition meant. I think to the benefactors of British imperialism, a ‘state of nature’ was anything that came from a place that was ‘other’ than their idea of ‘civilised’. This ‘othering’ is tinted with racist and classist projections, particularly directed at the places from which the more ‘exotic’ specimens were collected.

As I write, I become aware of my increasing use of quotations to imply that I think my word choice should be taken with a pinch of salt. I wonder whether this assumption is presumptuous, taking the reader to be aligned with my views from the get-go, prepared to nod along. Please write in if you disagree with my interpretations

I’ve written this to remind myself as much as my readers of a shred of the background over which any writing about natural history museums must take place. I hope in the coming months I will be able to continue adding to that tapestry with case by case examples from each institution I visit. What I want to claw at is an understanding of the context which allowed for natural history specimens to be viewed as ‘other’ from cultural heritage, and thus largely excluded from conversations around repatriation , decolonisation, and the western pillage of the global south. The truth is that my fixation with natural history specimens stems less from a scientific interest than a morbid fascination: from the knowledge that it is socially acceptable for me to look at a 300 year old corpse behind glass, and that it’s acceptable, even encouraged, for young children to do the same. When the glass bead eyes of a tiger killed in in the 19th century stare back at me, when its skin, kept dust free through the eons by dedicated volunteers, ripples in my imagination, when his claws grasp the faux plastic grass and his teeth slice carefully monitored air as they bare at me in a snarl, who is watching who? I feel seen, dissected and laid open, by the animals in vitrines. They send rivulets of shame down my spine because I know they should have been eaten centuries ago by detritivores, bones resting in a rainforest which probably no longer exists. Instead, they are re-animated and paraded as informants for their kind, like drugged up and puppeteered national representatives. They are markers of the unevenness of history, of a timeline that jumps and starts and snags on the beak of a great auk.

If you’ve gotten this far through, thank you for listening to me ramble. Although I’m meant to be writing about contemporary museums, as I wrote this piece I was taken with the whim of doing a month long series where I unpick museums which no longer exist. I’m excited by the prospect…but I want to hear if anyone else is too…so write in what you’d rather read 📖

P>S> Surprise photograph: here’s the lunch menu at the Natural History Museum sometime during the early 20th c.

*Best example of a museum that demonstrates the ‘pomp and exotica’ I describe is Picadilly’s Egyptian Hall which I will be writing about very, very soon*

See Nature and culture: Objects, disciplines and the Manchester Museum by Samuel J. M. M. Alberti for explanations of this phenomenon with specific reference to the Manchester Museum.

A general guide to the British Museum (Natural History), Cromwell Road, London, S.W. : with plans and a view of the building. 1886.

Kaufmann, Thomas DaCosta. "Remarks on the Collections of Rudolf II: The Kunstkammer as a Form of Representatio." Art Journal 38, no. 1 (1978): 22-28. Accessed April 21, 2020. doi: 10.2307/776251.

British Museum, Natural History. General Guide, 1931.

Oxford Languages, accessed via Google in August 2021.