Glass Eyes and Seeds

What actually counts as 'natural history'? This week I'm looking at the importance of contextualising an archive, using UCL's Galton collection as a case study.

This week I want to start a little bit differently, not looking at just one museum, but taking a delve into what actually counts as a ‘natural history’ collection. I threw out the ridiculous idea that I would write about one natural history collection each week at the start of the month, and copied the wikipedia list of museums in england which fit the bill without thinking too much about it. Last week I started with a museum which wasn’t on the list...classic. I wrote about the Hunterian museum, which sees itself as a medical collection - especially since much of their ‘natural history’ collections were destroyed during the Blitz. Their founder, John Hunter, was a doctor and the first surgical pathologist, and he considered his collection of items to be, more than anything, an instrument for teaching. The more I thought about defining my research boundaries, the blurrier they became. This week, I wanted to write about UCL’s geology collection, which I later found out is not currently accessible to the public. I wondered, was a rock ‘natural history’? Was a scientific instrument? Was a plant? Was a mummy? Was a syphillitic foot from 1783? In the only text to have survived Pliny, ‘Natural History’, he included sections on astronomy, mathematics, geography, ethnography, anthropology, human physiology, zoology, botany, agriculture, horticulture, pharmacology, mining, mineralogy, sculpture, art, and precious stones. This is much broader than how we think about the field today.

Throughout this series of essays, I will continuously refer back to the fact that the majority of England’s museum collections acquired the bulk of their artefacts during the Victorian period of colonial expansion and theft. I think it a relevant exercise to acknowledge the classical reverence possessed by many academics of the time. Plinian understandings of NH influenced the scope of both scientists and collectors. (Mirit et al., 2021) The exercise of collecting was intended to further knowledge of all areas of human culture, or more acutely - to create human culture for posterity through the rational principles of classical knowledge. “Projecting a bifurcation between nature and humans onto the past erases ways that natural history was also…about society.” (Mirit et al., 2021)

I went to a talk at the Natural History Museum in which Mitzi Tan, a climate justice activist from the Phillipines, spoke about her realisation that the Filipino plants owned by the NHM’s herbarium were part of her country’s natural history. They had been collected and stored as specimens, independent of the environment they came from, the people that had interacted with them for centuries, and the soil they grew in. This is the colonial paradox - in preservation, to de-historicise. To prioritise science over culture - ergo - to use science to explain and create history and culture. Last week I decided to write about a medical museum due to its large volume of animal specimens, many of which were not indigenous to the UK. John Hunter was a pioneer of comparative anatomy, and kept exotic pets for their future value as corpses to dissect and examine. For him they were largely void of cultural significance. As collecting progressed in the Victorian era, more and more creatures, plants, minerals, and instruments from all corners of the world became concentrated in London institutions.

I read a brilliant paper this week writers by Maria N. Miriti, Ariel J. Rawson, and Becky Mansfield that delved into importance of decolonising the human dimensions of ecology, argued through the lens of the lingering effects of ‘Natural History’ on the field. They defined NH loosely as '“the observational study of organisms in the habitats where they occur”. Using this definition, we can realise that most people’s experiences don’t fit this bill at all. Our institutions create spaces in which, separate from external reality, nature is constructed as a vision of the past.

It must have been so strange to be a contemporary of Darwin, or Soane (the founder of the Natural History Museum in London), and to have this paradoxical understanding of the new realities being discovered in colonial pursuit. The idea of imperial white progress relegates anything outside of it to the past - taxidermies it and puts it in a cabinet - even whilst it is still alive elsewhere. Today, we are still experiencing much of natural history through this framework. I’m writing this paper as a white woman, privileged enough to have had enough access and engagement with museums, and enough time to allow myself to think critically about this. As a white viewer, I also am set up to exist outside of the frameworks of natural history. Early collections existed to reinforce ideas about a “global hierarchy of cultures” (Miriti et al., 2021), positioning themselves as repositories of science. Science considered itself an observer rather than a creator, and taxonomy was something to be described, which existed objectively in the natural world. This allowed opinion to become fact, and to this day “shapes foundational…concepts. For example, natural history’s emphasis on pristine nature untouched by humans disregards or appropriates stewardship and knowledge of most of the world’s population.” (Miriti et al., 2021)

Victorian explorers who popularised the concept of ‘virgin earth’ were able to do so because they didn’t see non-white communities as being capable of generating significant ecological impact. They saw communities of ‘others’ as part of ecology, and themselves as removed, outside of it. Only from the outside could impact be generated and trajectory changing decisions be made. Equipped with this schema, British ‘bioprospectors’ rearranged and objectified nature, and not just for the sheer joy of it, but for useful mercantile pursuits and to cement the power of Empire. (Not so fun fact: The term ecology is attributed to German naturalist Ernst Haeckel. You may know him for his beautiful and trendy drawings of microscopic organisms - Taschen did a run of posters and printed a book on his work a few years ago. He was also a eugenicist

Scientists created authenticity for the new order they described through publicly accessible collections and the creation of ‘natural history’ museums. Here I think one of Miriti’s quotes says things better than I could.

"Collections are about separable objects, whether individual specimens or collective types such as species. These objects, or a sample of them, can be removed from their environments and then rearranged to various purposes both within and well beyond the collection itself. Indeed, natural history drove the rise of museums, herbariums, botanical gardens, and and zoos, all of which were not just for aesthetic enjoyment, but were, and remain, centres of scientific study.”. (Marati et al., 2021)

Although most people see natural history museums as something to visit on a weekend day out, a big part of what they continue to do behind the scenes is scientific research. With a focus on how research collections have been pillars for the creation of social agendas, as my case study today I want to look at the Galton collection at UCL. Charles Darwin’s half-cousin was a man named Francis Galton. Like Darwin, he was a fervent explorer. Galton is the originator of the behavioural genetics movement, and coined the term ‘Eugenics’ in his 1883 book ‘Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development’. It was Darwin’s publication of the cult classic ‘The Origin of Species’ that catalysed Galton’s life long obsession with modelling and understanding variation in human societies, and his works later re-influenced Darwin to write ‘The Descent of Man’. Although not available to view in person except by request to look at individual artefacts, the Galton collection is available to peruse online, where it is still labelled as being part of UCL’s ‘Eugenics Department’.

As I was questioning what counts as natural history, I thought about the effort to classify and at times, collect, members of societies and communities which existed outside of the North European bubble. The indiscriminate approach between cataloguing plants and cataloguing people in colonial pursuits made me think that the items in the Galton collection could, and really should, be seen as part of natural history. “His purist eugenic outlook was future oriented, based on an image of an uncontaminated distant past and haunted by a sense of the present as declining and in a state of exhaustion.” (Morris-Reich, 2016.)

This is a scale of hair samples in his collection, designed by Nazi scientist Eugen Fischer to categorise hair colours and textures. It was used to judge the relative ‘whiteness’, according to hair colour and texture, of mixed race people in what is now Namibia.” (Das, 2015.) The “scientific categorisation” of people, which was racism masquerading as objectivity, enabled the first genocide of the 20th century. A number of other items for this purpose are available to view online.

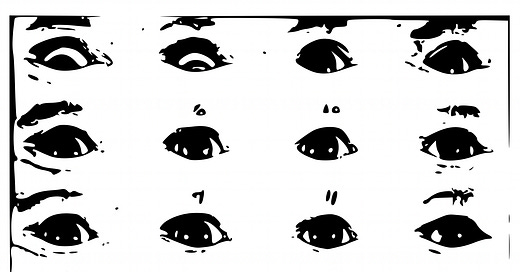

This is a tin of 16 glass eyes designed by Swiss anthropologist Rudolf Martin. His studies of the indigenous population of Tierra del Fuego (1893) and the Malays of the Malacca Peninsula (1905) established anthropological categorisation methods which would become accepted and used by eugenicists and Nazis. Items like these are physical markers of a corrupted past which continues to exert its presence on the present.

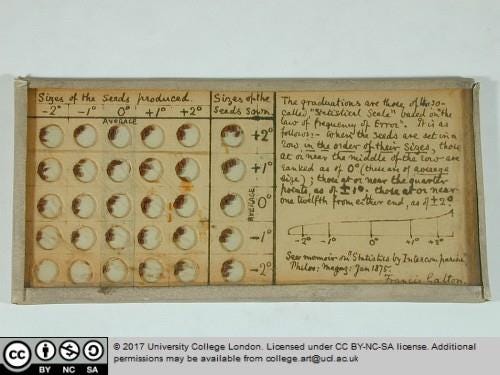

The Galton collection houses much more innocuous objects amidst the sinister ones. For example, examples of seeds used to explore genetic variation and the genetics behind inherited traits.

Scrolling through the items made me starkly aware of the importance of context - the image above displayed without its brothers, the hair tin and eyeball grid, seems like an innocent scientific experiment, perhaps the work of a keen gardener trying to improve his crop. However, seen as part of a network, the small circles of seeds become something much darker, preparatory experiments for the categorisation of humans. The translation of horticultural methodology to social anthropology shows the interdisciplinary nature of Victorian science, and makes stark the complex web of relations between items that might at first seem to be from different worlds. It’s important to remember these items continue to exist in the archives of contemporary universities, and to acknowledge that science as a discipline will never be able to scrub itself clean of the colonial supremacy it has enabled.

This is something I want to keep in mind in future issues of this blog, and this essay can act as a reference point for a way to think about to other collections I will write about.

In 2020 UCL conducted an inquiry into the history of eugenics at the university where they acknowledge that they “played a key role in enabling teaching and research to develop and disseminate eugenics and the theory of heredity.”, and the importance of Galton’s money on the development of the Eugenics department as UCL. The inquiry also found the institution had”the responsibility to illuminate the link between the ‘normality’ promoted by Galton’s eugenics and the discrimination and exclusion experienced today by those outside of that normality, eg. BAME students and disabled persons such as members of the deaf community.” The same year they also removed Galton’s name from one of their lecture theatres. In 2021, UCL issued a formal apology and a list of actions it was taking to de-colonise its curriculum. The artefacts continue to sit in store rooms. Some are yet to be photographed.

Bibliography:

MORRIS-REICH A. Anthropology, standardization and measurement: Rudolf Martin and anthropometric photography. The British Journal for the History of Science. 2013;46(3):487-516. doi:10.1017/S000708741200012X

Miriti, Maria N., Ariel J. Rawson, and Becky Mansfield. 2023. “ The History of Natural History and Race: Decolonizing Human Dimensions of Ecology.” Ecological Applications 33(1): e2748. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.2748

Subhadra Das. 2015. “Francis Galton and the History of Eugenics at UCL” https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/museums/2015/10/22/francis-galton-and-the-history-of-eugenics-at-ucl/

https://collections.ucl.ac.uk/Details/science/60000040

https://collections.ucl.ac.uk/Details/collect/60000479

https://collections.ucl.ac.uk/Details/collect/60000029

UCL Inquiry into the History of Eugenics https://www.ucl.ac.uk/provost/sites/provost/files/ucl_history_of_eugenics_inquiry_report.pdf

https://www.theguardian.com/education/2020/jun/19/ucl-renames-three-facilities-that-honoured-prominent-eugenicists

https://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/2021/jan/ucl-makes-formal-public-apology-its-history-and-legacy-eugenics